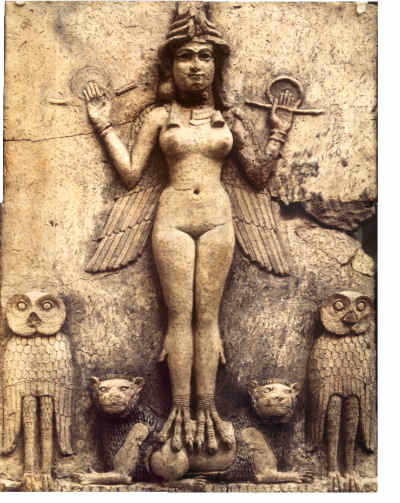

The Burney Relief : Innana, Ishtar, or Lilith?

One cannot escape the sense of contradiction expressed in this image of a goddess. At first glance one sees a beautiful young goddess, but as the eye follows down the realistic figure, the raptorial talons shock the imagination. This is no goddess! This is some sort of demon, perhaps a harpy. However, the serenity of the face and the symmetry of the posture are dignified in their composure. The body of the goddess is so naturalistic it could have been modeled from life, yet the owls are stilted in their stylization. The accentuated femininity of the figure suggests an earthy sexuality, but the rod and ring held above either shoulder are geometric abstractions and symbolic of universal laws.

The mix of styles and symbols suggests a hybrid divinity, a link between ancient archetypes and more recent devolutions. According to Baring and Cashford (The Myth of the Goddess 1991) it is probable that the plaque represents "Innana in her role as the goddess of sky, earth and underworld, Queen of the Great Above and the Great Below." They go on to explain that

"The Sumerian word for owl is ninna and the name Nin-ninna given to the goddess in her owl form meant 'Divine Lady Owl'. The ancient texts also give the Akkadian word kilili for Nin-ninna, and this name was one shared by Innana and Ishtar. (Perhaps kilili is the original derivation of Lilith, who, much later, in biblical times, is called 'night-owl or screech-owl'."They also note a possible connection to very ancient paleolithic (approximately 20,000 B.C.) symbols of the bird goddess.

Rafael Patai (The Hebrew Goddess 3rd ed. 1990) relates that in the Sumerian poem Gilgamesh and the Huluppu Tree, a she-demon named Lilith built her house in the Huluppu tree on the banks of the Euphrates before being routed by Gilgamesh. Patai then describes the Burney plaque:

"A Babylonian terra-cotta relief, roughly contemporary with the above poem, shows in what form Lilith was believed to appear to human eyes. She is slender, well shaped, beautiful and nude, with wings and owl-feet. She stands erect on two reclining lions which are turned away from each other and are flanked by owls. On her head she wears a cap embellished by several pairs of horns. In her hands she holds a ring and rod combination. Evidently this is no longer a lowly she-demon, but a goddess who tames wild beasts and, as shown by the owls on the reliefs, rules by night."

Patai asserts that Ishtar is the direct descendent of the Sumerian Innana. The Babylonian Ishtar emphasizes the promiscuity of a divine harlot rather than the virginal queenship of Innana. So much so that when Ishtar descended to the Nether world (an Akkadian myth parallel to the Descent of Innana), "neither man nor beast copulated; when she emerged, all of them were again seized by sexual desire."

Wolkstein and Kramer (Innana: Queen of Heaven and Earth 1983) present a psychological comparison of Lilith and Innana in a discussion of Ereshkigal, goddess of the Underworld:

"Ereshkigal, the neglected side of Innana, has certain qualities that are similar to Lilith's. Both are connected to the nightime aspects of the feminine- the powerful, raging sexuality and the deep wounds accumulated from life's rejections- which seek solace in physical union only. Lilith usually flees from rejections; Ereshkigal withdraws 'underground.' In 'The Huluppu-Tree,' when Lilith could not have her own way, she resentfully and destructively smashed her own home. The powerful Lilith of Innana's adolescent days had to be sent away so Innana's life-exploring talents could be developed. But now that Innana has become queen of her city, wife to her beloved, mother to her children, she is more able to face what she has neglected: the instinctual, wounded, frightened parts of herself..."

Let us quote directly from Wolkstein and Kramer's translation of the Sumerian poem, The Descent of Innana, to get a picture of Innana herself as she enters the Underworld carying the me's, archetypal forms of personal and social life:

Neti, the chief gatekeeper of the kur, Entered the palace of Ereshkigal, the Queen of the Underworld, and said: "My Queen, a maid As tall as heaven, As wide as the earth, As strong as the foundation of the city wall, Waits outside the palace gates. She has gathered together the seven me, She has taken them into her hands. With the me in her possesion, she has prepared herself: On her head she wears the shugurra, the crown of the steppe. Across her forehead her dark locks are carefully arranged. Around her neck she wears the small lapis beads. At her breast she wears the double strand of beads. Her body is wrapped with the royal robe. Her eyes are daubed with the ointment called, 'Let him come, let him come.' Around her chest she wears the breast plate called 'Come, man, come!' On her wrist she wears the gold ring. In her hand she carries the lapis measuring rod and line." When Ereshkigal heard this, She slapped her thigh and bit her lip. She took the matter into her heart and dwelt on it.

From the foregoing it is clear that we have in the Burney relief an amalgamation of symbols and images that depict both Innana (the rod and ring, the shugurra crown, the lions, the owls, the beads and bracelets) and Lilith. Lilith's symbols are the draped wings, her frontal nakedness, owl-feet, and also the horned crown. Clearly, the figure is that of Lilith, but some of the symbols are associated with Innana/Ishtar. The Babylonian Ishtar usually has wings, but they are always outstretched, never folded as Lilith's. The overall message is one of active sexuality, fertility, and dominion over nature with all its inherent oppositions- birth and death, peace and violence, animal and human.

The "rod and the ring" have an oft repeated interpretation. They are frequently described as measuring or survey instruments that could be symbols of kingship because they are given by a god to a king to use in laying out the temple. Similarly, Innana gives the "pukku and mikku" to Gilgamesh in Gilgamesh and the Huluppu Tree, but he uses them unwisely, causing grief to the women of Uruk. So he loses them and they fall into the Underworld. Wolkstein and Kramer say (in a footnote on page 143) that "pukku and mikku" remain untranslated, but they may be symbols of kingship. Kramer (The Sumerians: Their History Character and Culture 1963) speculates that they may mean "drum and drumstick" respectively, and it was Gilgamesh's use of them to call the young men to war that grieved the women of Uruk.

There is another possibility. At least one stele (Wolkstein and Kramer 1983, pg 9) shows Nanna the Moon god presenting the rod and and ring to Ur-Nammu, a Sumerian King (Third Dynasty of Ur, c. 2050-1950 B.C.), and the ring is clearly attached to a long, loosely looped line and the tapered rod appears to be about one meter long in comparison to the human figures. The rod and ring look like real measuring instruments. The rod and ring held by Innana are not the same items. The looped line is missing and the rod is just a small stick. Following Kramer's suggestion of "drum and drum stick", maybe Innana's ring and stick are the mysterious mikku and pukku. Thus the ring and the stick might refer to female and male principles respectively, emphasizing the sexual symbolism of the Burney relief. Gilgamesh's misuse of the relationship they imply would explain the women's tears in Uruk.

As an aside, there could also be a connection to the Egyptian ankh, which is generally said to mean "life" and is carried in the hands of gods and goddesses. The ankh has a similar arrangement of an oval and a line. In the most general sense this symbol depicts another pair of opposites, encapsulation and connectivity and symbolizes the goddess' encapsulation of the natural world within her own body.

Bibliography

Baring, Anne and Jules Cashford. 1991. The Myth of the Goddess. Penguin/Arkana, London

Kramer, Samuel Noah. 1963. The Sumerians: Their History Character and Culture. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Oppenheim, A. Leo. 1977. Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Patai, Rafael. 1990. The Hebrew Goddess 3rd ed. Wayne State University Press, Detroit

Wolkstein, Diane and Samuel Noah Kramer. 1983. Innana: Queen of Heaven and Earth. Harper and Row, New York